Episode 12: Jackson Pollock’s “Number 10, 1949” (1949)

[01:01]

VOICE 1: Well… Um, what I see is uh, an oblong canvas and the artist has taken paint that drips, that’s liquid-y dripping, not thick, from a palette, and just thr-, swir-, thr-, swirling it and throwing it and… and dabbing it and spotting it all over, but in a very, um, semi-controlled way so that it has a rhythm that is not accidental. I mean, it’s not accidental how this all worked out.

VOICE 2: Black, green, white, red, bluish, greenish, it kind a looks like writing when the black…

VOICE 3: Yeah?

VOICE 2: make an O and an A and an… another A… uh, W. It kind of makes me feel lost in the painting.

VOICE 3: Yeah. [laughs]

VOICE 2: Like I’m in the painting and it make me feel lost.

[02:02]

VOICE 4: It’s looks like sort of uh, almost religious dripping of the brush in circles around around and around and…

TAMAR: You were doing with your right hand when you were describing Pollock…

VOICE 4: Oh, uh, I was moving it in a circle, I think, right? [laughs] I mean, I dunno, it was like very subconscious, so… [laughs] I was moving it in a circle.

It’s a very physical, uh, reaction. And I that’s, when you think about how tortured he was and how emotional it is, of course you have to have some sort of physical visceral reaction.

VOICE 5: To me this is kind of, expressing a chaos, kind of controlled chaos in a way because altogether it looks crazy and chaotic and random but if you kind of separate the colors you can see almost patterns in the way he composed this painting.

VOICE 6: It’s like [a lick?] in free jazz because if you try to listen to the whole, you won’t understand. But if you just pay attention to one instrument, it sort of makes more sense. Like if you’re just listening to the, to one sax that’s playing a lot of very beautiful melodies but in the context of everything it’s just a mess.

VOICE 7: Yeah.

[03:13]

Intro credits.

[03:54]

So you want to know something neat? You can’t explain how an accordion works without moving your arms. Go ahead, try it. Or better yet, make a friend try it. Someone once mentioned this to me in passing when we were in high school, and weirdly enough, it really stuck with me. I guess because it was always amazing to me, a visual and verbal thinker pretty much from the womb, to imagine that there are some things that can really only be explained kinesthetically, more with your body than with your words. And explaining this accordion, your hands take on a life of their own, and you realize that it’s just so much more efficient to move your arms back and forth than to try to find the language to explain it.

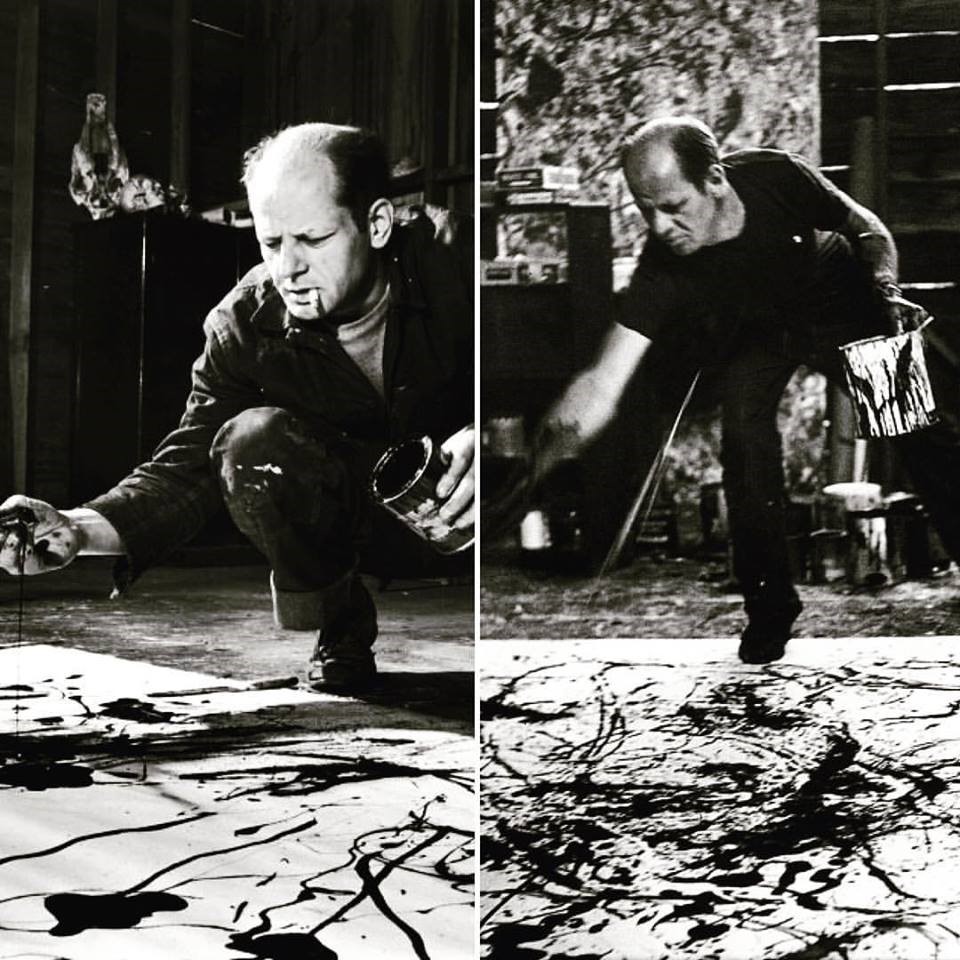

And I realized, in asking museum visitors to describe the work of Jackson Pollock, that if it’s hard enough to explain an accordion without moving, it’s almost impossible to explain Pollock’s paintings. These canvases are bursting with a kind of dynamic energy that gets into your feet. Following one brushstroke, or, more likely, one long attenuated drip, means tracking it along the painting, up and down and around, like a freshly unknotted balloon full of air whipping senselessly across the room. Because Pollock is action. His own movement is one and the same with the paint. We can trace the drips, from the canvas to the one-two punch of paint that is both flicked off a stick and poured directly from a can, and follow it straight up back to the arm in action that flicked and poured. To view a Pollock is to view Pollock, hovering and squatting and hunkering and crouching over his canvases, a cigarette hanging out of his mouth. See how many verbs it takes to make up for you not seeing my flailing arms right now? I mean, really, writing about Pollock is just inefficient.

[06:15]

So what’s going on here? What is the point of these wild, spun honey nests of drips? Well, to begin with, some context. If you’ve heard of Jackson Pollock, then you’ve probably heard of the movement that he is synonymous with: Abstract Expressionism. Now let’s take just a minute and unpack that name. It should ring a bell, because we’ve explored Abstraction when we looked at Mondrian, and we’ve explored Expressionism when we looked at Kirchner. And if there’s anything that I would have hoped that you took away from those episodes is that they are polar opposites. Expressionism is looking trauma square in the eye: it is unfiltered, raw, emotional, and specific. Abstraction, on the other hand, is a kind of transcendence away from and above the trauma to a place that is tidy, harmonious, and universal. The fundamental conceit of each movement is wholly at odds with the other. So how can Abstract Expressionism be a thing?

[07:26]

First things first, it’s important to note that plenty of artists whose styles are seemingly at odds are given this Abstract Expressionist label, from Pollock to Mark Rothko to Franz Kline to Willem DeKooning. All of these artists banded together as members of the New York School, a collective that formed in the 1940s when artists were fleeing Europe and taking refuge in the United States. This had a significant but not unsurprising consequence for art history: Paris, the heretofore unrivaled capital of modernism, was forced to relinquish its hold, and New York became the center of the art world. Abstract Expressionism was the first big movement following this shift, and was therefore a uniquely transitional, aesthetically-disjointed movement that basically restarted the clock. If you major in art history and your focus is on Modernism, then 1950, and Pollock representing for the Americans, tends to be the bookend.

Pollock, "Troubled Queen" (1945)

But what united these Abstract Expressionist artists, much more than subject matter – or, more appropriately, the lack of subject matter – is energy. We can define energy here by the explosive canvases that are so specific and iconic to Pollock’s later abstract style, but also in the deeply spiritual sense: so many Abstract Expressionists felt that they were painting a kind of universal, collective spiritual unconscious. Pollock in particular underwent Jungian psychoanalysis as part of his psychiatric treatment for his alcoholism in 1938. This exposure to the writings of Carl Jung, who espoused, among other things, the integration of opposites – conscious and unconscious, order and disorder—resulted in, for Pollock, an almost obsessive exploration of unconscious symbolism. His early works are teeming with symbols and juxtapositions, surrealist and fantastical, males and females, as he tried to work through these treatments on the canvas.

[09:47]

But as time went on, representation gave way to an abstract lens onto this collective unconscious. And again, let’s first unpack that phrase. Like Abstract Expressionism, collective unconscious should be a contradiction in terms. This idea that our deeply personal subconscious – our own subjectivity, my own unique me – is something that we all share should be conceptually impossible. And yet…it’s pretty fundamental to being human. Because, as Monty Python and the Life of Brian taught us, we are all individuals. And attempting to capture this on a canvas isn’t actually so unlike what Picasso, who was neither abstract nor an Expressionist, was getting at in Analytic Cubism. There, he was taking a step back, objectively painting our own subjective perspectives onto the world. Here, Pollock takes a step in, painting his own emotions, his own subjectivity, throwing himself quite literally into his canvas, and yet, when we as viewers take a step back, it’s something that we can all relate to. He creates a universality that appeals to all of us on a primal level.

[11:15]

Pollock in action (literally!)

This is partially because, like I said before, we so deeply empathize with his process. Not necessarily emotionally – believe me, you’re not missing out something if Pollock doesn’t leave you feeling crappy inside. I mean physically. Viscerally, even. Toe-tappingly. Consider the painting technique. It was revolutionary enough when the Impressionists showed their brushstrokes, taking a firm stand that paintings were painted, you know, by painters, and no longer trying to varnish away their brushstrokes, their fingerprints. Now Pollock has taken this further, by making each brushstroke, or drip onto the canvas, a direct product of his own physical action. You don’t get this kind of thrown drip without the immediacy of an arm flicking it. That arm is so present, we can feel it.

And then there’s the physicality of how he approached the canvas: he physically entered his paintings by placing the canvas on the floor and walking around it and on it – some works have cigarette butts and paint chips and other bits of trash ground into the paint from his footsteps. This was actually a style he developed from watching Navajo artisans demonstrate sand paintings, pouring colored sand from their clenched fists onto a flat surface from above—a powerful a way of being, in Pollock’s words, “more a part of the painting.”

[13:01]

And there are elements, and outcomes, of this approach that echo the abstraction of Mondrian: you can’t maintain hierarchy in a painting, the fore-, middle- or background, when you’re entering it from all sides. And then Pollock started to abandon titles, a classic Abstraction move, in favor of numbering the paintings; as his wife, the artist Lee Krasner said, “numbers are neutral.” Here, we’ve got #10, from the year 1949, which we are meant to view without any associations cluttering up our experience. And like abstraction in its purest form, there is indeed nothing being represented in this painting, only lines that, in Pollock’s words, were “freed” from narrative—classic abstraction language, the idea that narrative is a burden that we’ve been liberated from. Here, there’s nothing to recognize or unpack. Instead, we’re left with deeply balanced chaos, a Jungian mix of control and utter lack of control, a canvas that you must resist the urge to read and simply give yourself over to. Like I said, classic abstraction.

[14:25]

But like any abstraction, there’s a world of ideas and even emotions – either emotions denied or, here, emotions indulged – bubbling beneath the surface. This is where we tap into the Expressionist part of Abstract Expressionism. And, moreover, this is where we witness the emotions of a painter who spent his life unraveling—and whose ethos couldn’t have been more different from Mondrian—try to make sense of the horrors and irrationalities of a post-World War II world. Remember that Mondrian believed that the role of art as a response to trauma was to go above, not in. Pollock dove in body and mind, heart and soul, laying his emotional state bare on the canvas.

But it would be a mistake to write Pollock off a temperamental drunk who was simply using the canvas as an outlet for his fury. For all of their chaos, his paintings were painted with deep intention. Although he said he often immersed himself in a trancelike, spiritual state when he painted, playing with the element of chance, he didn’t like to think of his drips as accidents. Rather, they were controlled, and enormously aesthetically balanced; I doubt these paintings would be half so compelling if they weren’t. As you follow the trajectory of individual lines across this canvas, there is a wonderful sense of symmetry and gracefulness. When you step back and take it all in at once, the gestural black lines spasm and plume and burst beautifully to and fro, like dancers in motion, while the various layers of color jump forward and retreat back behind others, creating a pulsing cadence and flow. It takes a tremendous amount of control and a keen eye to paint abstraction that evokes wild abandon so elegantly. And Pollock, who had the rare treat of being a hugely important artist in his lifetime, knew how thin the line was between perceived chaos and actual chaos, and wrestled with it until his death in a drunken car accident in 1956 at the age of 44. He writes, “The painting has a life of its own, and I try to let it come through. It is only when I lose contact that the result is a mess. Otherwise there is a pure harmony, an easy give and take, and the painting comes out well.”

[17:25]

And you feel this, standing in front of a Pollock canvas, this harmonious give and take. It’s energetic, but it’s not aggressive; it’s powerful, but it’s not upsetting. There are plenty of artists in the 20th century who delight in making their viewers uncomfortable, but Pollock wasn’t one of them. There’s something gracious in his restraint, his privileging of balance, so that we tap our toes and sway our hips as we look, but we don’t actually experience the same emotional angst that he did. Of course, it’s right there in the bio, and in the pre-loaded cultural associations with Pollock and his booze and his temperament that we bring to one of his paintings. Between his own spiritual associations and his aesthetic influences and his personal emotional hell underpinning these drips, there’s certainly enough to dive into, to write about, to explore, to explain. But then, it’s just so much more efficient to move.

[18:48]

End credits.

[20:04]

Next time on The Lonely Palette…

VOICE 1: I would say it looks like a view out over the rooftops in, I guess it says Brooklyn. It’s from a bay window, and what you get is a sense that the person sitting in the rocking chair is, just looking at something in her lap rather than at the scenery. It’s, uh, a little bit lonely.

VOICE 2: You can see her contemplating, you know, the day changing and um, the light in the room.

VOICE 3: I like Hopper because I feel, I feel like most of his work is painted at the same time of day, there’s always this very like, sharp light.

I’ve caught myself staring out windows plenty of times, so… I can, I can kind of relate, I guess, a little bit.

[21:11]